Overview

Overview

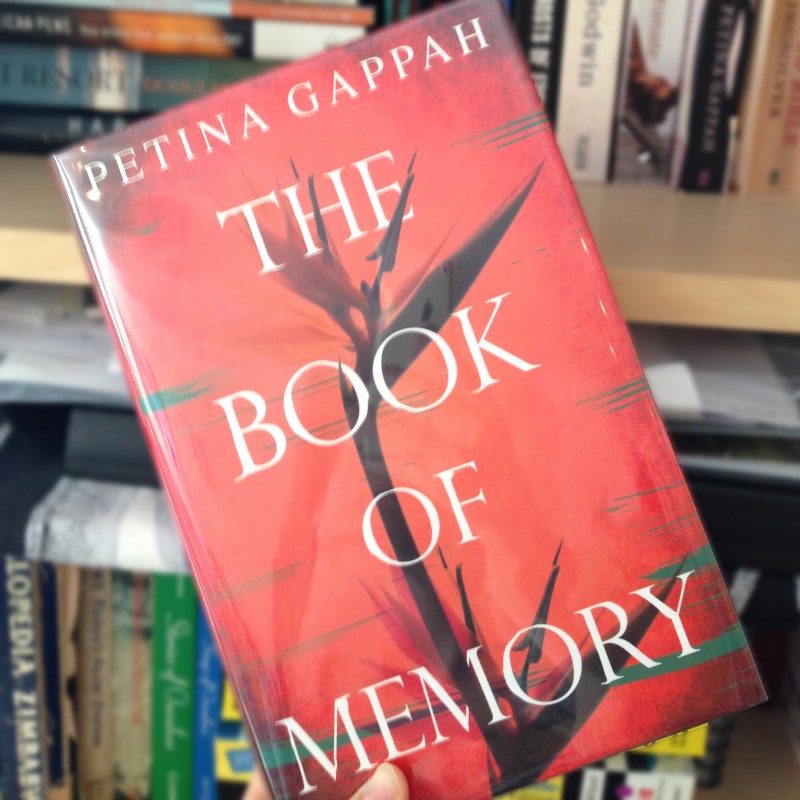

- Title and author: The Book of Memory by Petina Gappah

- Genre: Fiction

- Quick summary: An albino woman, Memory, is on death row in a maximum-security prison in Zimbabwe. She has been convicted with the murder of her adopted father. She writes to an American journalist about the events leading up to her conviction, and about her time in prison.

- Why read it?: Read it for the humour. Read it for the insight into what it may have been like for an albino girl living in Zimbabwe in the 1980s. Read it to meet some fascinating characters in Chikurubi Prison, from baby-killers to fraudsters. Read it so that you can start reading it again, and unwrap all that this book has to offer.

- Published September 2015 by Faber & Faber

- Buy it from Amazon or direct from the publisher

Review

The Book of Memory tells the story of a Zimbabwean albino woman, Memory, as she writes to American journalist, Linda, explaining how she came to be in prison for murdering her adopted father.

The letter style of the book is one way of making the story more accessible to a non-Zimbabwean audience. Memory sometimes explains some of the nuances of her culture and society to Linda, adding to our understanding. There are still some aspects that may go over readers’ heads though, such as the pieces of Shona dialogue that are scattered throughout the book. Rather than being put off by the untranslated text, readers should grapple with this as another layer of meaning, considering why Gappah chose to keep it in the novel.

We read stories to be transported to another time, another life, to look through another’s eyes. We are given that, and much more, in The Book of Memory. Laughing with Memory at the prison guards’ hairstyles, scaring the other inmates by carrying around a chameleon (an animal surrounded by superstition), watching the children play games on Mharapara street … Petina Gappah has a talent for painting characters that we know and can enjoy, despite us perhaps never having stepped foot in a township or a prison.

From the outset, there are a number of factors that pull you into the story: the unusual setting (a Zimbabwean prison), the character (an albino woman) and the mystery (did she really kill her father?). As you continue to read, you come to realise that you are also being enveloped into a deeper world of superstition and fatalism. Memory is haunted by nightmares of a Njuzu, an avenging spirit, which she cannot seem to escape.

Memory is well educated and articulate: she has had a good high school education at a Zimbabwean Convent school, then studied and worked in Europe’s universities for ten years. She is well-travelled and intelligent, and views others with a wry, disconnected humour.

Her observations of the other prison inmates are portrayed through a lens of wit rather than of deprecation. Having spent her early years in a poor township outside Harare, she has an understanding of the breeding ground from which her fellow inmates came. The characters are indeed absorbing and thought-provoking. For example, there is Mavis, who was jailed before the country became independent and thus has never known what a liberated Zimbabwe was like. There is Verity, who defrauded a European embassy of over half a million Euros by creating fake organisations such as the “Advancement and Empowerment of the Girl Child”.

As well as describing her current time in Chikurubi Prison, Memory writes about her past: how she, a township girl, came to be sold to a white man, and how she came to be convicted of murdering him. The narrative moves between the past and the present like the mythical, slithering water creature that comes to Memory in her nightmares.She says:

I am … laying out the threads that have pulled my life together, to see just where this one connects with that one or crosses with the other, to see how they form the tapestry from which I will stand back to get a better view.

Dark stories of witchcraft and superstition infiltrate much of the book, from goblins to witch doctors. Much of it is traditionally African in nature, but some is Western, such as the Greek Chimera. There is also misguided religion, presented to us in the form of Pentecostal Baptists and Pharasaic prison guards. This blend of cultures is much like Memory’s own identity: a mixture of black and white, Zimbabwean and European, a Shona Njuzu and Greek Chimera.

The superstition in the book culminates in the form of the Njuzu, which haunts Memory and carries her subconscious along a dark tunnel for much of the book. It is this that I enjoyed most: the theme of fatalism that Gappah has built into the narrative. This concept is best summed up by the character of Lloyd, Memory’s adopted father:

To have a fatalistic sense of life is to hold that our destiny is out of the control of any human being and that non-human actors will always determine the outcomes.

This is both comforting and terrifying … we have no control, and are carried along by a tide we cannot control.

In addition to the theme of fatalism, the novel also explores ideas of race, culture, education, identity, guilt, love and memory. I couldn’t help but notice some inconsistencies and stretches of the imagination, which are detailed in the Analysis below, but these didn’t stop me from engaging with the novel and enjoying its vibrant depiction of Zimbabwe in the 1980s−2000s, much of which brought back memories of my own childhood.

Summary

The Book of Memory is a humorous, insightful tale about a woman on the periphery of two cultures. It is filled with symbolism, metaphor and meaning, uncoiling itself to you like the water spirit that lurks through most of the novel.

Buy The Book of Memory from Amazon or direct from the publisher.

[button link=”http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/057129684X/ref=as_li_qf_sp_asin_il_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1634&creative=6738&creativeASIN=057129684X&linkCode=as2&tag=greazimbguid-21″]View it on Amazon[/button]

Read more articles on books about Zimbabwe.

A further analysis of the book is below. Warning: Please note that the analysis contains plot spoilers, so do not read beyond this point if you haven’t yet read the book.

Analysis

Analysis

Warning: Please note that the analysis contains plot spoilers, so do not read beyond this point if you haven’t yet read the book.

This book encourages active, analytical reading, which led me to the following observations and questions:

- Memory’s parents gave her this name. Yet there is an irony in that they shared few memories of their own with her: she knows almost nothing of her grandparents or ancestral home. She does, however, know much more about Lloyd’s ancestors.

- Memory’s love for Lloyd is a sweet-smelling fragrance throughout the novel. It was love for Lloyd that made Memory cover up his cause of death, and what got her into prison in the first place. It was concern for how people saw him, his reputation. Perhaps it was her guilt over the Zenzo incident too. Memory’s final words in her notebook are dedicated to Lloyd, too. When she gets out of prison, the first place she wants to visit is his final resting place.

- Q: In Chapter 3 Memory says that she is the youngest in a family of three. This is confusing, because there are two living children (Joyi and Memory) and two dead ones (Gift and Moreblessings). Gift died when he was young – we don’t know exactly how young, but old enough to have a photograph taken of him. Moreblessings also died young. Which one has been discounted and why? We may assume that Memory has discounted Gift because she cannot remember him. Yet when we meet Zenzo, Memory says that he, like her, was the third-born child. This indicates that she does count Gift because he was the first born and Moreblessings was the fourth born. So we are still left in the dark about which three children in her family she originally counted.

- Q: Why didn’t Memory dedicate more of her notebooks to aspects that would have helped her court case? She could have emphasized her birth certificate which had been in Lloyd’s possession, her school records which must have been addressed to Lloyd, perhaps the health records which must have shown that Lloyd had been Memory’s guardian. We are told in Chapter 2 that she is writing in the notebooks to aid her appeal to the Supreme Court, but she doesn’t devote much of her writing to proving her innocence. This interrupts the imagined reality about the reason for her writing, but perhaps the narrative is all the better for it. It is perhaps far more interesting for us to hear about Memory’s childhood than her strategy to build a legal case.

- Q: In the ten years that Memory has been out of the country, didn’t she save enough money to enable her to gain access to a better lawyer?

- Memory finds some happiness in her prison life by giving Loveness’ daughters the gift that Lloyd had given to her: education.

- Q: Can we read Chikurubi Prison, with its rules only known to those on the inside, as a metaphor for Zimbabwe?

- The idea of disappearing, of being lost in the darkness is repeated: the family photograph taken before Mobhi died which was left in pieces and then lost forever; the hopelessness of the prison setting; the Biblical Psalm about our days being numbered; the Njuzu; the dreams of drowning; the fact that she is on death row during the entirety of her narrating the story (“I know that I am laughing into the darkness”). These all seem to foreshadow an ominous fate for Memory in the first part of the book.

- On the theme of fatalism, so many things are out of Memory’s control: her skin colour, her parents’ history, Lloyd becoming her guardian. Even her trial was affected by political events: after the farm invasions, the judge was eager to show the world that justice was being done for this white man’s murder at least. The economic situation of the country meant there was no pathologist to do a postmortem which would have been evidence for Memory’s innocence.

- The idea of being pulled along by a force bigger than ourselves can be seen as a metaphor for the experience of reading as a whole. We as readers are subject to the whim of the writer, who can steer us in any direction s/he chooses.

- Often, time is not specified in the novel. Memory’s notebook entries are not dated; we aren’t told the exact year of her birth or her sentencing. We are told that she was a child in the 1980s and we go from there. Timelines are as slippery as the intangible Njuzu that haunts her.

- Q: Some details are contradictory, for example, Memory says in Part 2, Chapter 12 that her last day of freedom was on the last Friday of November. Then in the next chapter she says she was arrested on the second last Friday in November. Is this an oversight or an intentional demonstration of Memory’s hazy mind? She herself acknowledges “all the treachery of [her] imperfect recall”.

- Q: The death of Lloyd, and Memory’s actions surrounding it, also leave questions in my mind and seem like a stretch of the imagination, although I accept that she had been in a panicked state. If Memory wanted to protect Lloyd’s reputation, surely she just needed to put clothes on him, and moved his laptop, and it would have looked like a straightforward suicide? How did she shoot him in the back from a distance? Had she propped his dead body face first against something? This would be quite a difficult thing to do. How did she know how to check that his gun was loaded, turn the safety off and shoot him, without missing, from a distance, without having used a gun before?

- Q: Memory’s elder sister Joy is re-introduced near the end of the story. Joy’s revelation changes the tone of the book and brings to light the truths about Memory’s past. However the revelation also raises questions. We are told that Lloyd agreed to take in Memory when she was nine years old, and to look after her until her mother was well, indicating a short-term arrangement. We are also told that Memory’s parents died around the time that she was falling in love with Zenzo, when she was seventeen. This means that Lloyd looked after Memory for around eight years before their relationship was interrupted. Had Lloyd wondered what had happened to her father? Had he communicate with her father during that time? We can understand that Lloyd was a sensitive man who surely wouldn’t have wanted to cut Memory off from her father, or even the knowledge of him, for such a long time. Lloyd was reticent but not mute. He had spoken to Memory about difficult subjects, such as her albinism, so it is hard to believe he wouldn’t have spoken to her at all about this, despite her mother’s illness. We are told that he said he would tell her more “when the time was right” but it is a stretch to think he would have denied her of this part of knowledge of her identity, despite her deflections, for so long.

- Q: When Memory and Lloyd had made peace after her return to Zimbabwe, why did Lloyd never broach the subject of her parents or ask if she had read his letter?

- We are not told whether or not Memory’s appeal is successful, and we do not know what her fate will be. Memory’s final notebook ends – she cannot tell the end of her story because it is not yet finished.

- Despite the lack of resolution, Memory discovers truths about her past that cause her to resolve to survive – and perhaps this choice is the most important type of freedom.

- The narrative steered us towards an ominous future, but when Memory discovers the truth about how she came to live with Lloyd, the tone changes, and we can be hopeful that the dark forces might not devour her after all.

As with all content on this website, this material is copyrighted. If you quote from this article, please always cite GreatZimbabweGuide.com as your source.

Leave a Reply